Enough Already About The Next Seattle Mayor — What About Dow?

All that newly elected King County Executive Dow Constantine has to worry about is this:

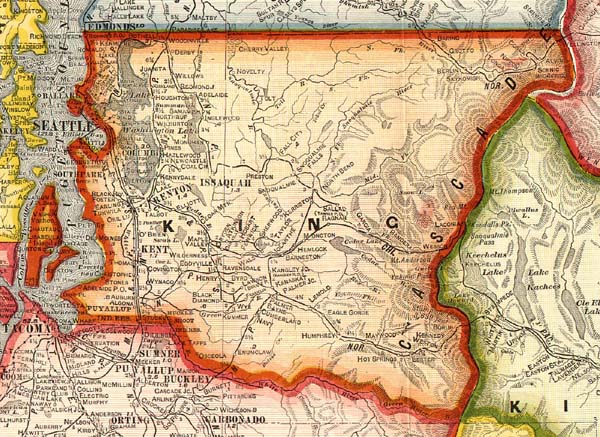

King County’s 2009 estimated population is 1,909,300—that’s about three and a half Seattle’s, and 29 percent of the State’s total population. The County produces just under half of the State’s total industry earnings. It covers nearly twice the land area of the State of Rhode Island, and encompasses six watersheds, the State’s second largest lake, part of a major mountain range, and extensive marine coastline.

King County is known for being a liberal hotbed, but political viewpoints range widely. In particular, many residents of the rural parts of the County believe that County government tends to be too dominated by the interests of Seattle and its nearby suburbs—a sentiment that has led to two intiatives to split the County.

The County’s Critical Areas Ordinance (CAO) is the poster child for the tension between urban and rural King County. Rural landowners perceive it as unfairly onerous regulation imposed by urbanites who don’t understand or appreciate the rural way of life. Environmental interest groups—most of which are based in Seattle—believe the CAO is essential for fostering the long-term ecological health of the region. And Dow Constantine has taken plenty of heat for his involvement with the CAO, even though he led the effort to modify Ron Sims’ original proposal in response to the concerns of rural landowners.

King County also has a massively consequential impact on the region through its operation of Metro Transit, which, based on 2009 ridership stats, is the eighth largest public transit system in the nation. Metro buses are the workhorses that have enabled Seattle to achieve a remarkably high transit commute mode share of 18 percent. And even as we build more light rail, Metro buses will continue to be the County’s transit workhorses for a long time to come, and as such will be a critical factor in reducing car dependence as the region grows.

All in all, King County embodies the full spectrum of challenges to achieving a sustainable future at the regional scale: the yin-yang of urban and rural. Our cities cannot become sustainable in a vacuum—they affect, and are affected by the surrounding region. And therein lies the importance of a visionary King County government, and the great potential for progress with a guy like Constantine at the helm.

The County has been making forward-thinking moves on many fronts in recent years, including sustainability indicators, green building, transfer of development rights, and perhaps most notably, the nation’s first legislation aimed at regulating the greenhouse gas emissions associated with development. And the time is ripe for Dow Constantine boldly push such programs further, and also be bold about new policy that will tap latent sustainability synergies in the County’s diverse people and places.  For example, how about a program that includes greenhouse gas emissions in the transfer of development rights equation?

And now for those masochistic few who may still be reading, I couldn’t end a post about regional planning without quoting what Lewis Mumford wrote 84 years ago:

The hope of the city lies outside itself. Focus your attention on the cities—in which more than half of us live—and the future is dismal. But lay aside the magnifying glass which reveals, for example, the hopelessness of Broadway and Forty-second Street, take up a reducing glass and look at the entire region in which New York lies. The city falls into focus. Forests in the hill-counties, water-power in the mid-state valleys, farmland in Connecticut, cranberry bogs in New Jersey, enter the picture. To think of all these acres as merely tributary to New York, to trace and strengthen the lines of the web in which the spider-city sits unchallenged, is again to miss the clue. But to think of the region as a whole and the city merely as one of its parts—that may hold promise.