Lewis Mumford’s Crystal Ball

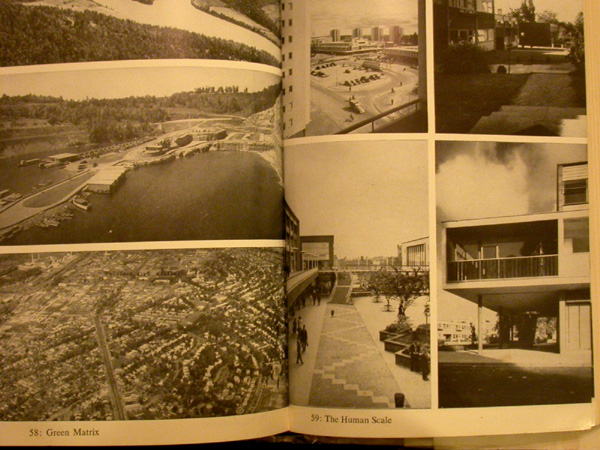

[Illustrations of “green matrix” and “the human scale” in Mumford’s The City in History, published in 1961]

He had a pretty good one, Mr. Mumford did. Here, from The City in History, is his reaction to the sprawling, car-dependent development that was already well under way 50 years ago:

“By building up sub-centers, based on pedestrian circulation, within the metropolitan region, a good part of urban transportation difficulties could have been obviated. To make the necessary journeys about the metropolis swift and efficient the number of unnecessary journeys–and the amount of their unnecessary length–must be decreased. Only by bringing work and home closer together can this be achieved.”

Nearly fifty years later, these ideas are finally seeping into mainstream consciousness.

And here’s Mumford going off on the new federal highway system in 1958, from The Urban Prospect:

“When the American people, through their Congress, voted last year for a twenty-six billion dollar highway program, the most charitable thing to assume about this action is that they hadn’t the faintest notion of what they were doing. Within the next fifteen years they will doubtless find out; but by that time it will be too late to correct all the damage to our cities and our countryside, to say nothing of the efficient organization of industry and transportation, that this ill-conceived and absurdly unbalanced program will have wrought.

“Yet if someone had foretold these consequences before this vast sum of money was pushed through Congress, under the specious guise of a national defense measure, it is doubtful whether our countrymen would have listened long enough to understand; or would even have been able to change their minds if they did understand. For the current American way of life is founded not just on motor transportation but on the religion of the motor car, and the sacrifices that people are prepared to make for the religion stand outside the realm of rational criticism. Perhaps the only thing that could bring Americans to their senses would be a clear demonstration of the fact that their highway program will, eventually, wipe out the very area of freedom that the private motorcar promised to retain for them.

“As long as motorcars were few in number, he who had one was king: he could go where he pleased and halt where he pleased; and this machine itself appeared as a compensatory device for enlarging an ego which had been shrunken by our very success in mechanization. That sense of freedom and power remains a fact today only in low density areas, in the open country; the popularity of this method of escape has ruined the promise it once held forth. In using the car to flee from the metropolis the motorist finds that he has merely transferred congestion to the highway; and when he reaches his destination, in a distant suburb, he finds that the countryside he sought has disappeared: beyond him, thanks to the motorway, lies only another suburb, just as dull as his own. To have a minimum amount of communication and sociability in this spread-out life, his wife becomes a taxi driver by daily occupation, and the amount of money it costs to keep this whole system running leaves him with shamefully overcrowded, understaffed schools, inadequate police, poorly serviced hospitals, underspaced recreation areas, ill-supported libraries.

“In short, the American has sacrificed his life as a whole to the motorcar, like someone who, demented with passion, wrecks his home in order to lavish his income on a capricious mistress who promises delights he can only occasionally enjoy.”

And so on. Same as it ever was, but worse.

If you’re still with me, here’s one more to show that Mumford’s crystal ball was not pure gloom and doom, a glimmer of hope from near the end of The City in History (keep in mind the context of 1961):

“But happily life has one predictable attribute: it is full of surprises. At the last moment–and our generation may in fact be close to the last moment–the purposes and projects that will redeem our present aimless dynamism may gain the upper hand. When that happens, obstacles that now seem insuperable will melt away; and the vast sums of money and energy, the massive efforts of science and technics, which now go into the building of nuclear bombs, space rockets, and a hundred other cunning devices directly or indirectly attached to dehumanized and demoralized goals, will be released for the recultivation of the earth and the rebuilding of cities: above all, for the replenishment of the human personality. If once the sterile dreams and sadistic nightmares that obsess the ruling elite are banished, there will be such a release of human vitality as will make the Renascence seem almost a stillbirth.”