Transit-Oriented Communities: A Blueprint for Washington State

What you best be doing next Tuesday, October 27, from 4 to 8pm, is this: Drinking beer and talking the wonk about transit-oriented communities. Because that’s when there’s gonna be a release party and AIA exhibit opening for a new report called Transit-Oriented Communities: A Blueprint for Washington State, written by Futurewise and its partners GGLO and Transportation Choices Coalition. Details here and here.

Some may recall a little brouhaha over HB1490, a.k.a. the TOD bill, during the 2009 legislative session, when the evil social engineers at Futurewise tried to mandate that every Seattle neighborhood would have to become as dense as Mumbai or lose City snow-plow service. Or something.

Seriously though, the Blueprint was inspired in part by the HB1490 experience, which demonstrated the need to educate the public and address the concerns of community members. The report reviews the social and environmental benefits of TOC, proposes a typology and performance metrics, examines the potential for TOC on the ground in the Central Puget Sound region, and proposes policy actions that would help foster TOC.

This report is chock full of wholesome wonky/planful/urban designy goodness—I should know because I helped write it. Since in a past life I was an electrical engineering researcher, I took on a lot of the techy stuff, such as energy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. My science background has left the indelible stamp of a skeptic on my brain, but the more I learned about the relationships between GHGs and land-use patterns, the stronger the case became.

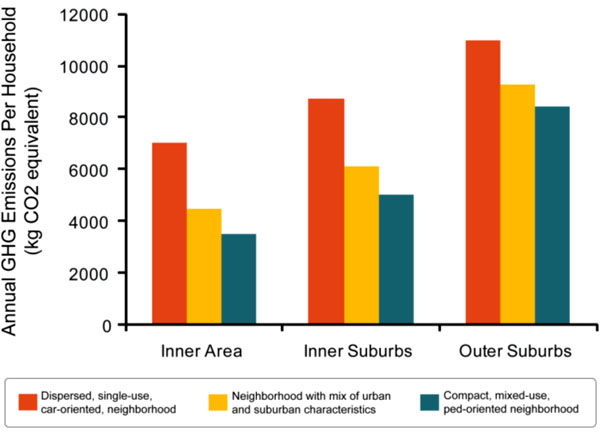

Below is a little sample from the “Evidence” section of the Blueprint, that goes with the bar chart porn at the top of the post:

A 2000 Canadian study of the Toronto area modeled the effects of socioeconomic makeup, location, and neighborhood design on GHG emissions from vehicles.  The results are summarized above, and show that the both urban form and distance to the central business district have a significant impact on household GHG emissions. For example, in the “inner area†case, GHG emissions from households in a neo-traditional neighborhood (residential density = 102 units per acre) are half that of households in the traditional suburban neighborhood (residential density = 9 units per acre).