…look in the mirror. All those scorn-reaping townhouses are simply a reflection of the state of our culture. There is no alien invasion involved here. Townhouses are financed, regulated, designed, built, bought, and lived in by members of our community. The trouble is, the community is broken. And no amount of building code updates or panel discussions can fix that.

In a broken community you are likely to find both builders and buyers without strong connections to place. And so builders become more inclined to produce shoddy, overbearing townhouses because they know they won’t be around to face the neighbors. And buyers tend to not so much mind living in a home that sequesters them from community life on the street — exhibit A: the six-foot cedar fence along the front property line. Should we be at all surprised when the the most individualistic culture in human history produces housing that has little respect for the common good?

Weak community bonds also enable the domination of a purely economic perspective, encouraging builders to see townhouses solely as a means to make money, while encouraging buyers to see them as an investment rather than a home. We Americans are always on our way to somewhere else, to something better, so the townhouse becomes nothing more than a vehicle to keep up with housing prices until we can get that dream house and really start living.

As for the sorry state of townhouse architectural design, the cause couldn’t be any more obvious: Our culture just doesn’t care very much about architecture. Today, utilitarianism and bottom line economics are what drive “design,” if you can call it that. The buildings still tell the story of our culture, but the story reads like a technical manual — it has no poetry, no soul. If more people valued design, if they sought something more culturally meaningful than a utilitarian box with openings for a home, then that’s what the market would deliver.

In terms of urban design, the typical townhouses currently going up in Seattle’s neighborhoods are a choice example of how we can’t have it both ways. We want dense, affordable, livable urban housing, yet we also want maximally convenient access to our cars. And so we try to make the townhouse do both, and we end up with the all too familiar compromised schlock. We simply don’t have the money and we don’t have the urban land to accommodate a car in every housing unit.

The townhouse, or more generally, the rowhouse, is one of the oldest and most successful urban building types in history. Our culture has the dubious distinction of being the first to so effectively wreck it.

[ Historic London townhouses ]

Alright then: But all this is not to say that better building code would be useless for mitigating townhouse blight. And the single most effective code update that the City of Seattle could implement to help improve townhouse design would be to do away with parking requirements in all lowrise zones. Alas, of this, the City of Seattle shall not speak.

Townhouse garages take up space that could be lived in, increase unit cost, raise the building height, and relegate main living spaces to the 2nd floor, disconnecting residents from the street. Townhouse driveways take away green space, increase stormwater runoff, reduce the site area available for the buildings, and drastically limit the site design possibilities. In the typical configuration with the driveway running between buildings, the buildings tend to get squeezed outward as close the property lines as possible. Mandating even wider driveways, as is proposed in Seattle’s multifamily code update, will only result in more cases of townhouses beating up on neighboring buildings.

When so much of the site is given over to driveways, there is little space left over for yards. And this is a major reason why so many townhouses have tall front yard fences. If the only place that isn’t paved is the front yard, then it will need a fence if people want a private bit of outside space. If the community was more closely knit, perhaps people wouldn’t feel they needed a fence to keep their BBQ from being stolen. Instead, the fence reinforces community breakdown and the vicious cycle continues.

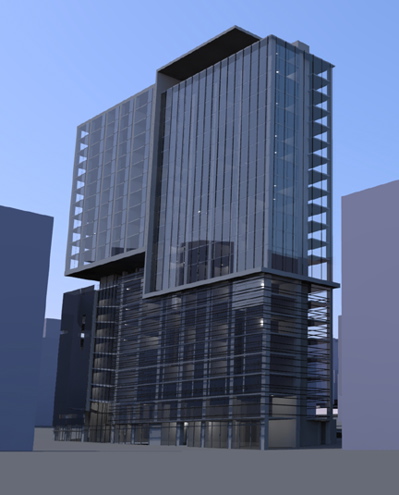

Removing parking requirements might also encourage developers to try other building types such as small apartments, that would help break the near monopoly of new townhouses in lowrise zones. I suspect that those who are disgusted with townhouses would find the apartment discussed here much less objectionable — but there is no parking in it.

The thing is, even if the City removed parking requirements, change would be slow because in the short term, most builders would put parking in their projects anyway. But we should at least give them the option — now. It is inevitable that eventually, parking requirements will be revoked across the entire City of Seattle. Global warming and peak oil guarantee it. And the sooner it is done, the more pain we’ll avoid in the long term.

And all apologies, but I’m going to continue to repeat myself and leave you with this 1961 Lewis Mumford quote:

“The right to access every building in the city by private motorcar, in an age when everyone owns such a vehicle, is actually the right to destroy the city.â€

Â