For those who have recovered from the mayoral primaries, you may have noticed that the Waxman-Markey Climate

Bill, otherwise known as H.R. 2454, the American Clean Energy and Security Act, has moved on to the Senate… and the debate over how best to dilute it is about to start.Â

The Bill is huge. It is 1,428 pages of pure economic bliss for financial behemoths like Goldman Sachs and a moral victory for folks who have been pummeled enough to understand that for the federal government even a small step in the right direction is a big thing. Greenpeace and others oppose the bill because it simply does not go far enough for the environment (which is true), decrying the “this is the best we can do†mentality as an indictment of the whole legislative system.  But, they neglect to acknowledge that at least this is a start with promise. It’s not going to solve our gargantuan problems, but, as one optimist notes, it “gives us a framework to build on, and puts us on the path to what science says we need.”Â

So, what is so promising, aside from greenish platitudes? If you want the scoop by someone who really knows, stop reading and go here. Or here. Or just read the thing yourself. Notice the obnoxiously large line spacing and the glacially scaled margins. You’d think that a climate preservation bill could have said to hell with legislative layout standards in the name of resource conservation – just this once. But alas…Â

This Bill is not only about big picture policy – it also has real implications for our cities. Here is my take on two of the tops:

1. Mo money? Yes.  Mo Problems? Maybe…Â

This is the obvious part. Thinking optimistically, Waxman-Markey manufactures a brand new revenue stream that can be directed towards fixing the environment we broke. More cynically, it is the opening salvo in the race to win the climate-industrial complex. Regardless of your perspective, however, Waxman-Markey will open up an entirely new global market, allowing cities, regional authorities, nations, international consortiums, and anyone else with some vestige of faith in the resiliency of the US financial system to raise revenue by trading carbon debt. There is tremendous opportunity here. Imagine a TDR system for all new development that is based on trading embodied-energy credits related to construction and building operations – a potential boon for preservationists, proponents of adaptive reuse, and eco-conscious yimfy’s.  Possible? Maybe. Bel-Red set one recent local precedent earlier this year, allowing density transfers between the City of Bellevue and King County.  Others are being looked at too. There may be little market for this today, but eventually there will be.  When W-M passes, which seems likely, we will all have to work diligently to ensure that the environment actually comes out on top. Otherwise, we’re all done for, and density – no matter how seductive, or profit – no matter how great, won’t matter.Â

2. National Energy Code

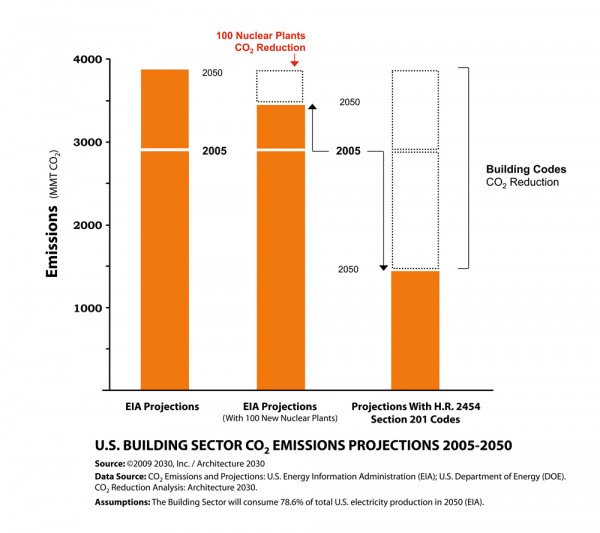

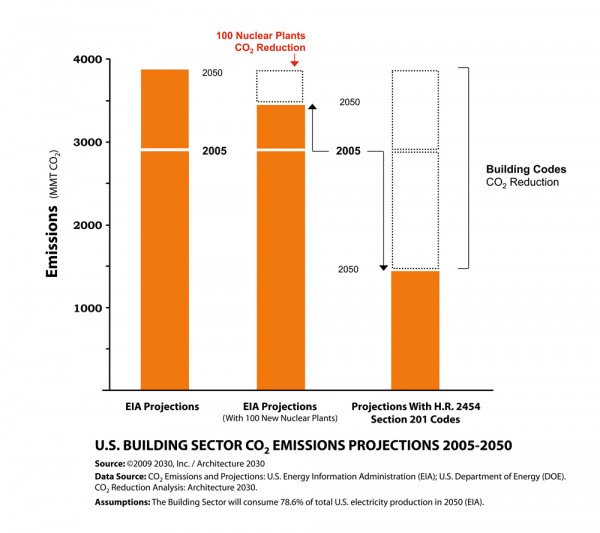

This is a little more wonky. For cities today, the most important part of the bill is the building energy code language, otherwise known as Section 201, which mandates a new National Building Energy Code and federal enforcement of state and local compliance. Since buildings account for about 40% of energy consumption in the US (add about 12% more if you consider the building materials industry), recalibrating the laws that govern their construction is some of the lowest hanging fruit from a policy perspective. Edward Mazria, founder of Architecture 2030, notes:

“The codes … achieve more than six times the emissions reductions of 100 nuclear power plants… [and] …accomplish all of this at a fraction of the cost.â€

Wow. If this is even half right, nothing may do more to put our built environment on the path to energy smartitude. Good thing Washington State has already started.

But more efficient energy codes are only the beginning, as they deal with only one slice of the US building pie – building systems. Revamped general building codes are the next step. The International Code Council (ICC), which creates the general building codes adopted by most US cities, is working on a project to develop a new Green Building Code, albeit initially focused only on commercial buildings. The aim is to substantially reduce buildings’ share of energy consumption through passive measures and to contribute to a suite of coordinated codes that harness synergies between building components, construction systems, energy systems, and development types. LEED, BuiltGreen, and a host of other private programs have attempted to get at this for years, but each has been limited by voluntary participation, a lack of standardization, and an as yet emerging understanding about how many green features will actually perform in the field. Firms that are actually evaluating the post-occupancy performance of buildings that they design are learning how to anticipate many of these aberrations, which helps. But there is still a long way to go. Hopefully, as the Green Code develops, we can put the lessons learned all in one place.

Where this could be pushing us, of course, is the holy grail of plannerly wonkish enviro grass roots urbanism: the Performance-Based Code. A flexible, climate-friendly platform for city making. Too bad it doesn’t exist.Â

But it did, once, sort of, in a relationary form that delineated building envelopes and uses by adjacencies and interface with the streetscape, rather than by “as-of-right,†or zone. Granted, the scale, politics, market, and technologies involved were a bit different back in 550 CE than they are today, but the overall concept remains a compelling one. Some are trying to re-establish it today – albeit in a much updated version, based how urban areas operatate. West 8, the Netherlands’ landscape urbanism starchitects, borrowed from the idea to code the sexy little wharf block at Borneo Sporenburg, as a pilot project. And that turned out ok – if you look at it as a petri dish sized experiment for a larger urban system.  After a series of tests about how design-side factors could impact urban and architectural performance, the firm narrowed the code mandates down to roughly three: parcel size (which they conveniently got to choose because the development was brand new), land-side streetwall, and a 30-50% interior void (courtyard) space. There were a few other minor conditions, but that’s about it. The project acheived a remarkable variety while contributing to a cohesive, dense, urban streetscape. No word on energy consumption, but with all the operable windows, internal daylighting, and party wall conditions, I bet it’s not too bad. Metropolitan scale endeavors would have to be much more complex.

If you think of cities as the backdrop for life, then the mechanism that enables the backdrop to function is a bit like a computer’s operating system. Zoning and codes are the programming languages which allow neighborhoods and buildings – the ‘wares in this metaphor – to develop, relate, and interact. Unfortunately, from an environmental and use perspective, we are all running on Euclid v1.0. And nationally speaking, we live with the results every day.  A sea of climate-sapping, auto-oriented non-chitecture and a few mediocre 5 over 1 ‘bread loafs’ bobbing about here and there. Form-based Codes, ‘Smart Codes,’ and well thought out design guidelines have raised (or are raising) the level of average in many places, but they are still the equivalent of Microsoft giving you a prepackaged list of options for your Windows ‘theme.’ I run ‘Classic.’ Yeah. Please don’t judge me.

Some places, like Portland, have pioneered performance-oriented urban districts, and others have suggested policy language to incentivize their creation. But neither really gets at the core of the issue: the coding platform itself. Instead, both serve as patches (albeit highly innovative patches) for a byzantine OS.Â

So, why not just rewrite the OS? Well, it is not that simple of course. Politics, economics, and just about everything that physically exists today each has a vested stake in the status quo, which, as you can imagine, creates a substantial amount of inertia. Also, there is the fact that “performance-based†implies that someone or something must be the decider regarding who has performed well and who has not. Who’s going to volunteer for that?! Until we develop some standard metrics for evaluation, I imagine there will be few takers.

Oh, and there’s this… last Tuesday, the National Academy of Sciences reported that no matter how progressive we get with our urban coding strategies, we are totally and irreversibly screwed when it comes to climate change. There is simply too much sprawl for denser, better performing cities to provide a meaningful offset.  Even though the same report says that Portland’s growth policies are working. Hmmm.

So, back to W-M and our City.

Where is Seattle in all of this? What leadership can we offer? Well, we have a Copenhagen fetish – that’s cool I guess, because Copenhagen is cool and very green. We have the Seattle Climate Partnership, which we are still figuring out what to do with. We have the Green Factor scorecard. We have created a thorough, data-driven pedestrian master plan with performance criteria at its core – Good. Also, we are at least considering amendments to our own zoning code. Like Waxman-Markey, those are a start.

Hey man, don’t you even try to sneak a quick, furtive glance into the entrance of the Lusty Lady. Cause in case you didn’t notice, that black and white orb hanging beneath the canopy on the

Hey man, don’t you even try to sneak a quick, furtive glance into the entrance of the Lusty Lady. Cause in case you didn’t notice, that black and white orb hanging beneath the canopy on the  Though the circumstances justifying surveillance may vary, in the end what it comes down to is that these cameras are band aid solutions that ask us to give up freedom in exchange for security. And in this case it wouldn’t be all that smug to add that we “deserve neither,” given the

Though the circumstances justifying surveillance may vary, in the end what it comes down to is that these cameras are band aid solutions that ask us to give up freedom in exchange for security. And in this case it wouldn’t be all that smug to add that we “deserve neither,” given the