[ Aerial photo of Thornton Place, as of March 13, 2009 ]

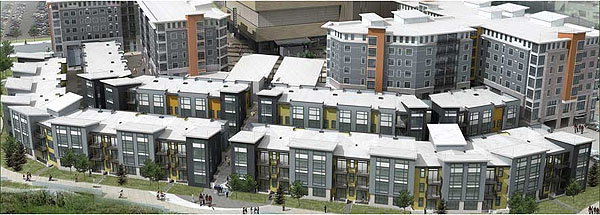

Cruising by Northgate Mall on I-5, the nearly completed Thornton Place evokes images of sci-fi outposts rising from the barren landscapes of distant planets. In reality, Thornton Place is, in fact, a daring pioneer in a built environment that is likewise hostile to human life. And the conversion of nine acres of asphalt into the development shown in the photo above is phenomenal accomplishment: Thornton Place is Seattle’s first real transit-oriented development (TOD).

Aye, it’s a big one: 109 condos, 278 apartments (20 percent affordable), a 14-screen cinema, 50,000 sf of retail, and a 143-units of senior housing, along with a new daylit section of Thornton Creek. The block is roughly 600 feet square — about twice the length of typical Seattle block.

Ideally, it would have been better to break up the block with bisecting streets, though some folks who object to the size of the project would seem to be under the impression that everything you need to know about urban development can be picked up from a few chapters of Jane Jacobs. Small-scale, incremental development is wonderful. But in some cases, big projects make sense, and Thornton Place is one of those cases.

Northgate has been targeted for growth by city planners for decades: It is a designated Urban Center, a bus transit hub and future light rail station area. But the existing car-oriented, single-use built environment around the mall is a highly unappealing site for small-scale mixed-used residential development — what developer would risk being the lonely pioneer amidst a sea of big box and parking lots? In contrast, a large project like Thornton Place creates a center of gravity powerful enough both to keep itself alive, and to be a catalyst for future adjacent development.

[ Thornton Place, rendering via Stellar Holdings ]

And no, Thornton Place will never be the ideal walkable community, but it gets about as close to that ideal as you could realistically expect, given its context. As mentioned above, reconnecting the existing street grid through the project would have been a good urban design move, but then who would pay for those streets? They ain’t cheap. For the Burien Town Square project — a similar pioneering outpost — the stars aligned to bring in $7 million in grants to pay for interior streets.

In any case, Northgate neighbors objected to through-streets over fears of increased traffic. And a north-south through-street would have interrupted the creek bed. All and all, given the circumstances, the Thornton Place plan does an admirable job of breaking down the block and creating a permeable site, with a dogleg street in the northwest corner, and numerous pedestrian walkways, most of which are permanent public easements.

The project includes 880 subterranean parking stalls, which sounds like a lot for a site next to a transit hub. But through no small amount of cajoling, the developer was able to convince the City and County to allow about 350 of those stalls to be shared as Metro Park&Ride stalls. This enabled a reduction of the total stall count to about 200 below what city code normally requires. At $40k a stall, that’s $8 million not spent on parking. You’d think shared parking arrangements like this would be a no-brainer, but they are still almost unheard of in Washington State.

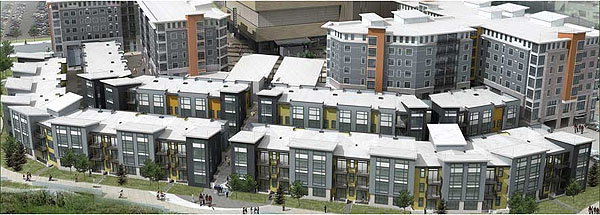

[ Rendering of Thornton Place interior open space ]

The intended social heart of the development is an internal plaza in the northwest quadrant (see rendering above). It’s a space that turns its back on the outside world, but was there really any choice when the outside world is currently a wasteland of giant mall parking lots? Given the density of residences and the draw of the movie theaters, this plaza has great potential to become a vibrant people place.

Obviously, the massive box of a cinema is the clunker of the project, and not only physically. Mega-retail that must by necessity draw from a wide geographical area is antithetical to pedestrian-oriented communities. Even though someday lots of people may ride the train to the movies, it still means other neighborhoods are likely to be deprived of a local theater.

The 2.5-acre landscaped area around the daylit creek provides an open space with a character opposite to that of the plaza: It’s green, relatively quiet, and extends to the outside borders of the project. When the landscape grows in and development starts to fill in across the streets, this open space will be a cherished amenity. And while the ecological contribution of the daylit creek to salmon habitat may be relatively minor, the symbolic value is immense.

Subtracting off the 2.5 acre open space and another one acre for the cinema, the net density for the project comes out to 96 dwelling units per acre. Remember how HB1490 proposed allowing at least 50 units/acre in high-capacity transit station areas? Here’s an example that about doubles that density with a combination of three and six story buildings — no high-rise necessary.

All said, what makes Thornton Place so noteworthy is also the biggest challenge to its success: the location. Market rate rents are expected to be just under $2/sf, while condos start at $300k for 600 sf. This pricing is competitive with similar housing in established neighborhoods like Ballard. Which would you choose?

But it would behoove us to figure out how to make developments like Thornton Place work. Large-scale mixed-use infill projects are likely to be the essential catalytic medicine for bringing transformational change to countless urban and suburban malls across the country.

Â